Daniela Seel was talking with Yevgenia Belorusets and Charlotte Warsen. Translated from German by Thomas Nießer.

Daniela Seel: Let’s start with something nice: What was your favorite moment of working together?

Charlotte Warsen: It was probably the jokes we were making as we went along… A lot of things did not work out for one reason or another and all taken together it was pretty funny.

Yevgenia Belorusets: The best moment for me was when we both understood what we could achieve here.

CW: When it became clear?

YB: Yes, when it became clear. That we had found a solution to the trap in which we had found ourselves.

DS: That is a pretty important keyword, trap. Why do you say trap?

YB: Because – for this project, you have to work with A female artist, a poet, whom you have never met, whom you do not know and about whom you know pretty little and whose way of working you really do not understand. This happened to me for the first time. And on top of that you have very limited time during which you have to complete something.

CW: You only have seven days, just before the event, but you have to announce weeks in advance what you intend to do, when indeed the whole point of the things is, to develop everything in this room, together, and emerging from the work process. And yet, you have to say in advance what you want to do.

YB: One accepts, perhaps in the hope to break the usual artistic practices through something unexpected. But for this really to happen is a great challenge.

DS: How did you go about it, how did you reach this point?

YB: The process consisted of many ‘no’s’, much that we did not want to do. For me it was clear that I did not want to do and event with a reading, that this is no longer of interest to me, that as an artist I cannot build a background for a reading. The format in itself is of no interest to me. Rather than looking for new formats, it was much more interesting to me to find new contents, which could be developed further in the conversation with Charlotte. And nevertheless, I find that almost by accident, we developed a new format as well, even though that was not our aim.

CW: Almost as a side effect… For me it was very similar. I really did not fancy that we build a backdrop and I then read in front of it and this makes it a different reading, because it has a particular backdrop. But, regarding the form, I had intended for a very long time to exhibit poems or to present as typeface on the wall. This is now the first time that I show a text on the wall and not projected and like in a museum, but like a written page, which is on the wall. And, I think I will carry on doing this.

YB: I have done this a number of times in exhibition rooms.

DS: With texts of your own?

YB: With my own texts.

DS: It seems to me that that is something which connects you, as you both do interdisciplinary work, in different forms and media.

YB: I think that what we really have in common are our literary and political backgrounds, similar reading materials, which inspire us in their content.

CW: Of course, everybody creates their own field of pictures and texts through which we move and there we have many overlaps. And now there are a thousand new books, which she recommended to me and a thousand texts, which I recommended to her, all of which we must now read over the coming months…

DS: Like you have already said, Yevgenia, it can appear to be a little odd, coming together with a stranger like this for such a short amount of time. You create something together, but then what happens next? Does it impact your own work, what do you take with you?

YB: We are considering making a book of it. Or further exhibitions and publications. It is a real shame: You work on delivering this message, and then it is only shown for such a short time. For visual art it is unbelievably short.

DS: Are these only ideas for the time being or do you already have something concrete?

YB: These are not just ideas, it is already concrete work, which we have done, in which we consider as to how this work can continue to exist after the exhibition.

DS: You have implied that your common springboard was more content-related than formal. What are your contents?

CW: Maybe they come from a similar reading history, which is very much interested in heterogeneous forms of text, from theory to poetry, and which we judge in a comparable way.

YB: If you ask for concrete elements of content, there are different layers in this exhibition. The first and most obvious layer is the political reality of two countries, which cannot be connected, but which become visible in their contrast. For me, it is about war and the reception of war, and I think for Charlotte as well.

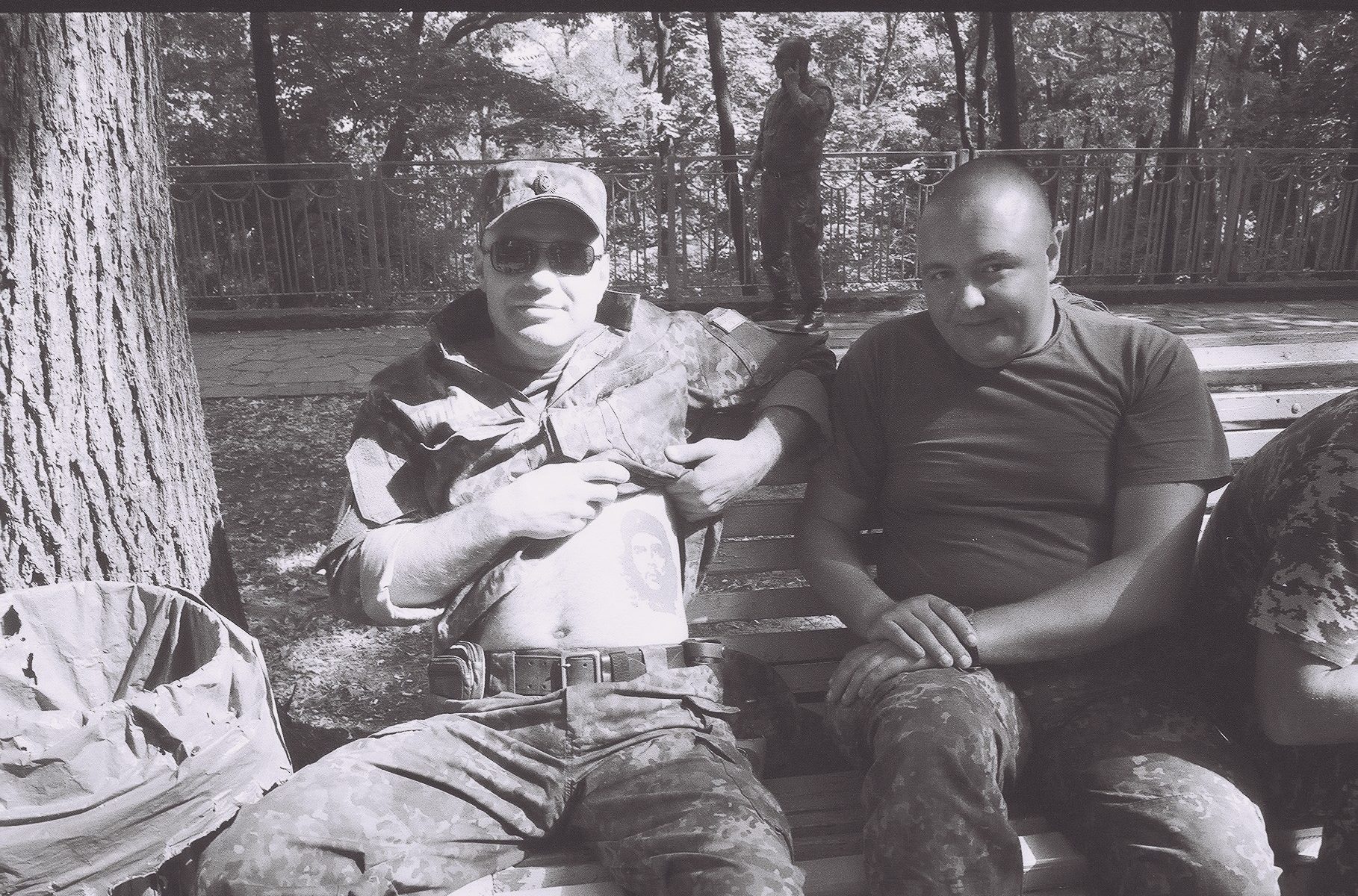

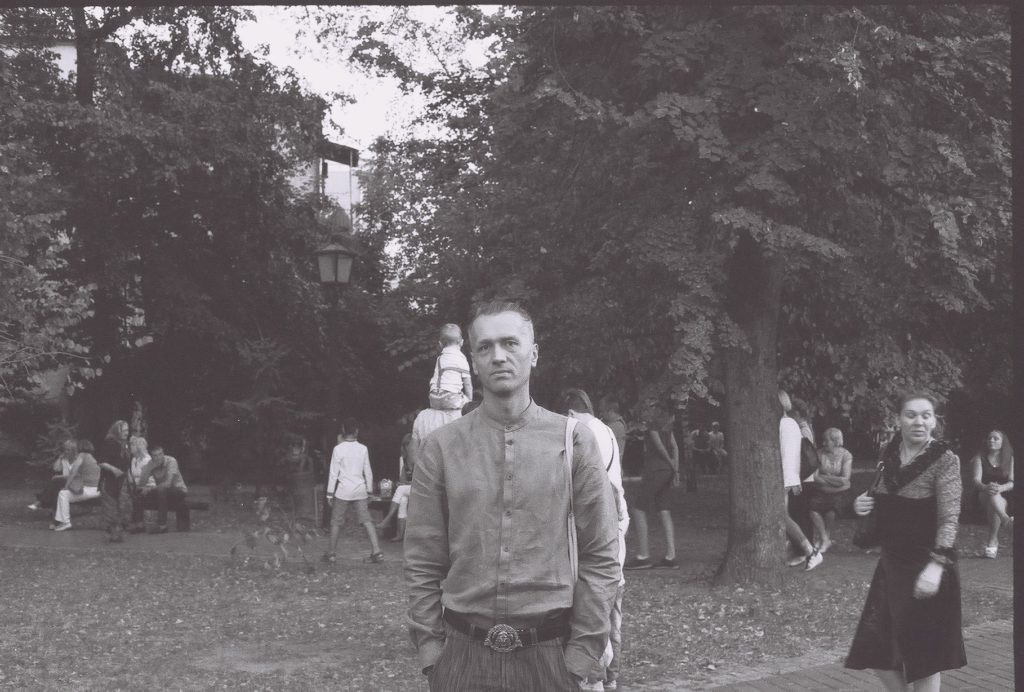

CW: Yevgenia had chosen a series of photos, which she had taken in a park in Kiev. Among other things one sees men in camouflage gear and one knows that has a connection to the war, without knowing the context, just by looking at the photos. And I wrote text, not to or emanating from the photos, but more about these images. Imagining myself, I am ambling in this park with my eyes wandering, standing in front of those photos and basically not knowing what I see there. How are the images composed, what details do I find, what talks to me, what does not tell me anything? Or what do I want to blank out?

YB: The text is very interesting as it also talks about the gaps in our perception when we look at something. I find that every event, especially if it is unbearable and dragging on like a chronic illness, will one day be invisible, in every society, not just in a neighbouring one as Germany is a neighbouring country of the Ukraine, all be it not immediately geographically. In the Ukraine herself, war gets out of sight. Why did I work in parks? They are places of recreation, almost all of them have remained as they were during the time of the Soviet Union, almost unchanged and they play a strange role in the urban space. In a poor society the park is one of the few places where different societal classes and differing realities meet. One could say they are a scene of life but even from this scene sometimes important elements are disappearing. I took this series during moments of the escalation of the war and during those days, it was warm at the time, many soldiers took to the park to relax and recover. They were soldiers, who had travelled home from Donbass, in the east, and who apparently just had stopped over in Kiev, perhaps to visit relatives or just for recuperation. And then one could see them in these parks. But that was only until 2016.

Charlotte’s poem is built in such a way that again and again one falls into something white, unspeakable, in breaks between words, into something that one cannot see or does not want to see. And my photo series is about these white and dark areas of reality. It is also good that one can read Charlotte’s poem in different ways, ways which one draws through the poem. She arranges the poem such that the reader always has a choice between two different elements. One cannot read the poem as rationally as a text of prose. The poems are visually built almost like hieroglyphics, so that they can be apprehended first as an image. And there is a seduction, or an undoing, to choose, which path through the poem one finds as the reader. And that is something that we play with in the exhibition as well.

Another layer of the exhibition is the talking about ways of seeing and reading. To experience this, you will have to come to the event and listen to the vocal guide through the exhibition.

CW: Yes, exactly, it is about a certain pathlessness of understanding and also about the fact that in Germany there is little knowledge about the war in the Ukraine and that likewise one can rest easy on not-understanding as to what different protagonists want and who pursues exactly what objectives. And what also interested me very much in Yevgenia’s photo series, and what I found particularly good, is the way how she deals with the situation that the more human lives a conflict costs, the more crass it is, the more pressure is mounting on visual artists to create images, which work as documentaries or which fulfil the expectation to say how it is or to convey certain facts.

YB: Or to take a stand, for example by supporting a party directly through certain kinds of photos.

CW: Or by generating closeness in the first place, which in the end isn’t there at all; bridging distance, not to stand remoteness, but to zoom in on something that possibly cannot be zoomed in on. And in this park closeness to what you see is not immediately clear. And this is then, what the text is just about. And about the question how one reads poetry in Germany and how one is generally used to reading a text or to approach a text as if it was a park or something in which you can move about. And it is not necessarily lines, rather passages in the text, from which you can move to other passages or move about in these white areas.

And then there is a third level or layer, and that is the guided tour, which we have announced. That is an audio tour through the exhibition. Would you like to say something about this?

YB: It is not simply and audio-tour, but a play with the reception of room and image and among other things also a conversation as to how we interpret photos and generally how we can misunderstand something. And what does the instruction of others mean, which accompanies us through exhibitions and territories of art and literature? The voice accompanies the viewer already from the entrance to the exhibition room to the exhibition room itself and guides from one picture to the next, through certain lines and passages in the text. And it also provokes the listener to stand up against this voice.

CW: The voice, which one has in the ear, is just as decisive as it is dishonest and encroaching, really, but also affectionate. One is taken by the hand.

DS: How did this text come about?

YB: We wrote the text for the guided-tour together.

DS: But the poems are also a part of the exhibition?

YB: A poem by Charlotte Warsen is a part of the exhibition, and the text of the guided-tour is another part.

DS: And the joint book project that you both have in mind, that would contain the photos and the poem and the text of the guided tour? Or would there also be a CD?

YB: No, I think it would only be the text.

CW: It was a pleasant time, when we simply sat together, here in this room and we started to work on the text, on the voice, which you carry with you through a button in your ear and which guides you through the exhibition, because we had very similar ideas about which breaks we want, which timbre of the voice we want, what we want to write, what we want to happen, what directions should be given…That was simple a very good joint process of writing.

DS: And you have done this since last Monday, since you have come together here?

CW: Exactly. What the walls look like, what the room looks like, we had already clarified. And then we walked together through the exhibition with chairs and we created the voice to it. It was an absolute ping-pong and a really good cooperation on a joint project, on a joint guided tour.

DS: And you then recorded this together?

CW: Exactly.

DS: How will it be done technologically – everybody who comes in gets a device?

CW: Actually, we wanted to have and official audio guide, such as you get in museums, such a big bone that you carry in your hand, with digits, and then you stand in front of a picture… But they are available in much bigger series only, you have to give notice much earlier, then they will make a recording on these devices. For that we would have needed to know months in advance what we wanted to have recorded. And this is why we now have a ‘slim version’, simply MP3 players. Of these we have so many that the room can still be entered, 15 pieces.

DS: In the announcement you talk already of dialogue and these so-called participatory techniques are indeed very much en vogue. Nevertheless, these practices are firmly determined, by the arrangement of the room, the artists; the freedom of participation is limited. I find the coercive aspect of it exciting, especially if it is a voice, which you cannot easily fight against, to which you cannot simply position yourself. And then you say that you want to provoke people to stand up against it.

YB: That as well, a little. We also wanted to create an adventure, an adventure of seeing. Once can stand up against this voice, but only if one listens to it, if one follows all the instructions. This is the key as to how one really can defend oneself. If one does not follow what the voice recommends, it hardly makes sense.

CW: The voice suggests interpretations, the voice suggests emotions and it also suggests affects. Of course, it does not conceal that. It is not an attempt to activate people, who appear too passive to that voice.

YB: If one listens to the voice then there is a way of freeing oneself from it.

DS: The documentary is ambivalent, of course. One says documentary as if it was objective, but – you already alluded to that – it is equally intentional. The claim even of saying that something is documentary more often than not has a propagandist background or shall be used for something specific or, as Charlotte explained, to create sentiments or closeness or as a corrective for politics. I like how you try to deal with this in its complexity. Could you expand this a bit more, the problem of the documentary and the demands on art?

YB: In my work I never deny the intention that I want to hint at something. For example, if you choose a topic and you talk about it then this is already propagandistic. I mean that I propagate that one looks at that direction, as a minimum. At the war, that is, or photography or of the documentary. But I feel that in this case it is important to understand what you do and that you use these mechanisms. Then you can sense how far you can go.

This photographic work is probably something unusual for me because the narrative is already broken here – like a poem by Charlotte Warsen. It is therefore very difficult to interpret it as a direct statement. But certain situations, confrontations cannot be avoided as running away is very cynical as well. The documentary in itself is already fictional as well, but we also carry responsibility for every fictional narrative, which we construct. And we always communicate something anyway, fictional or documentary or a bit documentary. I think that this project attempts to treat the documentary with irony but it nevertheless leaves the trace of the seen and tries to tell about it, subjective as it may be.

CW: I think that in talking about how political art is or how documentary art is there are some pseudo-dialectics. There is fiction, there is the documentary and then the next step is to say ‘ah, but the documentary is fictitious already etc. And that then turns into the ultimate that can be said about it. What often falls to the wayside in this is the timespan, which the viewing takes and the timespan, which is taken up by reading and the traces, which this leaves behind. The voice already has its timbre and it has means to exert pressure or to generate sentiment; the text again is doing something else; one moves from one of these places to a another one and then back again; and our idea was that it gets interwoven in such a way that it gets even more unclear and it is more about these ways themselves. Not so much the question: Where is the documentary or the bare facts, where is the realm of fantasy, even though they are commonly presented as opposed to one another.

YB: I think we were both looking for a clarity in the narrative itself. The narrative has a value in itself and with our guidance it becomes rather distinct. It has a ‘sujet’.

CW: I find that interesting as well when it is about poetry. What do we regard as a story? Traditionally, the narration is commonly attributed to novels or short stories etc. and then there is of course the question which one of the evoked sensations etc. is also part of a narrative, apart from a plot and spaces, which are described etc.

DS: In your self-description in the invitation you position your works between art and activism.

CW: The press release was already part of what we had planned. We did not know yet exactly what would happen here, but we did know already that it was rather about raising a problem about the whole thing – these are so horrible words, that is to make it more confusing rather than clearer, during the course of the work process. And we wanted to write a press release, which states clearly that it is here about a certain political conflict, an armed conflict. And this dialogue between pieces of work as well, all these are so empty clichés from press releases about art or Artist Statements. We just wanted to make a press release, which did not sound completely daft, but in one way very clear so that people would think, oh great, I just go to a political exhibition and there are a few poems thrown in, super.

YB: In the press release we did not want to talk about formal aspects, about the documentary or the museum aspect.

DS: This is now an aspect, which I also find really exciting: In talking about it both of you locate yourself in the visual arts and you say that takes up slogans and PR-bullshitbingo from the visual arts and you also say that the project is an exhibition…

CW: A guided tour.

DS: A guided tour. And yet, it is decidedly placed in a literary context. The Lettrétage is a house of literature and for CON_TEXT, going by the self-description of the whole project series, the emphasis lies indeed on text and literature. What do you think what effect this shift of the context has on dealing with your pieces of work?

YB: I write as well. Both of us work with texts.

CW: I would say the same: both of us we work with images as well as with words. Often, I cannot and do not want to separate this in my work – I can only talk for myself, but I think you experience this very similarly – and I think that many people feel the same. It is just that there are spaces and scenarios, which are assigned to the visual arts or to literature.

YB: Sometimes my exhibition take place in houses of literature. But in this case language – speech and text – play a key role anyway. This exhibition is dominated by the textual and the verbal. I think that an audience, that visits the house of literature to attend a literary event, will in this case not even sense that it is in exhibition rooms. We call it that because the room is created, and the arrangement is fixed. Nothing changes. It is not a reading, no theatrical action. That’s why we call it an exhibition.

CW: The idea of a guided tour reminds of formats, in which knowledge is imparted, facts are imparted, at a guided tour in a park, a museum etc. Here, you would put yourself the button into your ear and then you would receive precise announcements as to what you should look at first, what you should feel with it, what you see there and maybe that will not correspond to what you see and then comes the point at which you will stand in front of the window and you will be told, which park you see from the window.

YB: But we cannot now retell everything.