A personal report on the seventh CON_TEXT event with Rike Scheffler and Jochen Roller by Florian Neuner, translated from German by Elizabeth Toole

Any one of the masses of visitors packed into the documenta showrooms in Kassel could hardly fail to notice the striking disparity between the kind of reception warranted by the numerous works of art that are kept there and what is actually appreciated. Or rather, they would find themselves in the position, simply for reasons of time, to not be able to do justice to many of the works. Some of the films projected on screens and monitors are hours long. Other artists present visitors with entire archives and extensive documentations, which would require a considerable amount of time to read or even just somewhat adequately take in. Visitors usually burst into the film screening and leave again a few minutes later. The artists and curators either do not seem to mind this kind of reception or else they imagine an ideal recipient, who comes to Kassel with all the time in the world. When contemporary art meets spatial art, frictions often emerge, but sometimes chances for a changed perception also arise. To a certain extent, you could experience the reverse situation to the contemporary art presented in the exhibition rooms recently in the Lettrétage, an easily produced vocal acoustic space. The collaboration of author Rike Scheffler and choreographer Jochen Roller resulted in a new kind of performance. The two were invited to create an installation and completely transformed the Lettrétage, where contemporary art of literature is usually the focus, into an artistic space. The public they encountered there had to adjust at first to the unfamiliar situation of being involved with a multidimensional event, when they were invited in at 8pm.

At first, you might think that it was all about rubbish, like the preceding CON_TEXT event by Cristian Forte und Harald Muenz, the window next to the entrance was taped up with strips of shredded paper after all. Inside, under the window was a crate, also overflowing with strips of paper – not just any old bits of paper but ones clearly printed with text. A picture that might be interpreted as an expression of a rigid reduction and selection process, which may have preceded this installation. Similarly to Forte and Muenz, Roller and Scheffler work with greatly reduced linguistic material. Alongside other small interventions in the room, which are yet to be discussed, a rectangular section, cordoned off by gauze curtains, diagonally opposite the bar was actually the centre of the action. When the public entered the Lettrétage, the first thing they heard was a subtle soundscape of birdcalls. At some point human voices appeared to come from the area behind the curtains. That was the signal for the visitors to enter the sound installation behind the curtain and venture a glimpse into the area covered with foam and with six loud speakers hanging from the ceiling at different heights. On the soft floor, lined with foam, which also invited the visitors to sit or lie down, were sensors in various places marked with a clear invitation to ‘touch me’ It did not take the public long to experiment for themselves or to find out through cautious observation that touching these sensors played sound files. A female and a male voice recited fragments of poetry such as ‘A hungry moon’, ‘Something warm left lying around’, ‘Baden singsong’, ‘Tentatively opening pelvis’, ‘We remember it well’ or ‘How does the sound hit your skin?’

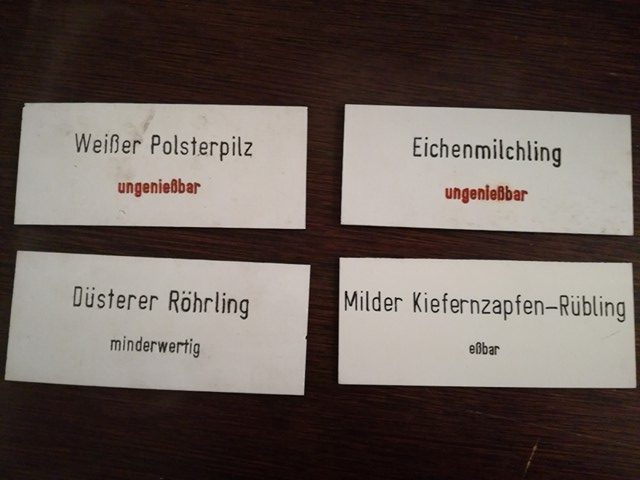

People’s instinct to play was soon awakened and a mesh of many overlapping voices could be heard – a relatively simple experimental setup which lead to complex and surprising situations. When you pressed the buttons several times, you could cut off the voices or interrupt them yourself. After perhaps half an hour, the sound of overlapping text fragments audibly started to dwindle and gaps and pauses emerged. The crowd moved to the bar or out to the yard, but returned perhaps once or twice to continue playing less proactively with the installation in a more intimate setting. Meanwhile, the artists were there in the background, mingling with the public and not revealing themselves. Roller and Scheffer added another layer to their interactive sound installation by placing placards on the floor next to the sensors, which read ’Suillus placidus (edible, very rare)‘, ’Lactarius torminosus (hot, edible after particular preparation) ‘, or ’Tricholoma focale (value unknown)‘. Mushrooms with these names really exist and together with the birdcalls in the background, you could really get the impression of being in the forest searching for the sound of voices. In a small cool box outside the actual sound installation were not only ice cubes but also notes with words like ‘BACK’, ‘MOON’, ‘SCENT’, or ‘SINGSONG’. A curtain also divided the front room from the corridor leading to the back room with toilet doors, with little boards fixed on them. ‘Pendulum suspension’, ‘hang up a nesting box’ alongside illustrations. The second back room was separated off with opaque material and was not used.

Termini technici, as the foundations, were the structural element that connected the installation with these other interventions. The title Rike Scheffler and Jochen Roller chose for their contribution was another such term, ‘memory foam’ is the name of plastics that have a so-called form-memory effect and can ‘recall’ past states after transforming. Had this work been displayed in the context of some art exhibition, the public would surely have got bored with it much quicker, they would not have experimented for so long with sounds and overlays and they would have had a much more limited experience with the sound installation. The clash of time and space art as part of the CON_TEXT series proved to give the audience an opportunity to pay more attention to a spatial installation than would have been possible in a different context.