Impressions by Ricoh Gerbl, translated from German by Elizabeth Toole

It is a Tuesday evening, just before 8pm. I am walking along the Mehringdamm. On my way to the Lettrétage. Author Kinga Tóth and illustrator Doro Billard are going to present the results of their collaboration. They had a week to get to grips with each other’s different forms of expression, or simply put to find a way to come together. This event, where literature encounters other art forms, is part of a series called CON_TEXT. Authors meet artists from a variety of fields and have to create something together. This evening the third outcome of such a ’collision’ will be presented to the public. I turn into the backyard. A few people are standing in front of the entrance, smoking.

I pull open the door, walk through the small lobby and notice that something is missing. Chairs. ”What? Am a supposed to stand for the entire evening? There has always been seating here. Every time I wanted to listen to an author, I have been able to sit down. And today I am not allowed to sit here passively and let voices wash over me?“ I am annoyed, and would like to complain. But to whom am I supposed I say, “Do you know that being able to sit is really relaxing and not being able to sit is really exhausting.” I look around for someone whom I could tell. I am especially on the lookout for someone who looks as though they would know where the chairs are hidden away. I am getting warm. I pull down the zip of my winter coat. I want to feel more air and less material around my body. My open coat cools me down a little, but it is not enough. I slip off the coat completely and put it down on top of a piano. There are no chair backs after all. My moaning seems unfair even to me.

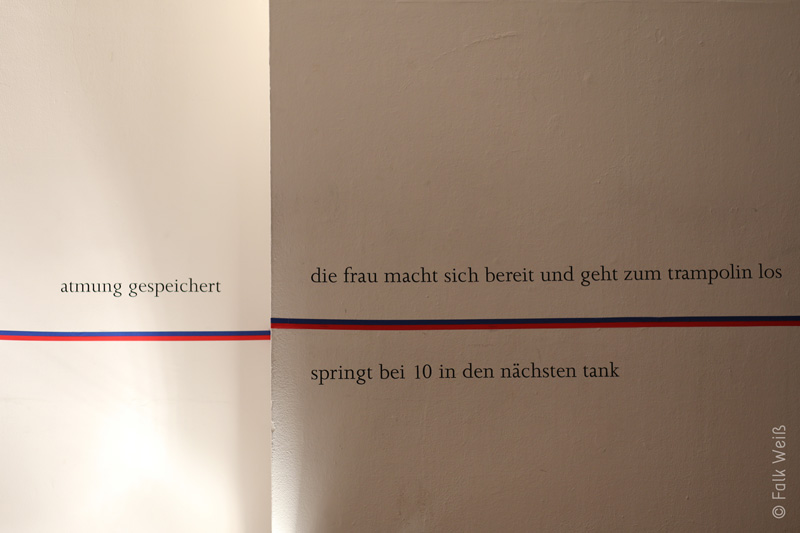

As I know for sure that in the past, I have also wished for such a reading to go a little differently, differently to what we know and have so often experienced. So I calm down, reconcile myself to the lack of chairs and consider giving this unusual presentation a chance. The first thing that strikes me are the sentences stuck to the walls in big black letters. I read one of them. It says, ‘Not everybody returns to the body‘. In the middle of the room is a bathtub. There is some water in it. Next to the bathtub is a pile of crumpled-up paper. Behind the bathtub there is another sentence on the wall. ’Just as you speak into the water in the tub, when your mouth is blocked, so they speak to me. I am on the floor of the tub and they want to reach me from above.‘ There are illustrations hanging on some of the walls. One shows objects from children’s playgrounds. Swings. Slides. In another illustration, I can make out surfaces of water. In a sketchbook lying on a table, there are more illustrations of water surfaces.

Kinga Tóth’s texts and Doro Billard’s illustrations enrich each other and can be read and understood as a whole. I try and read into the work what I can. A two-toned line extends through the whole room at approximately hip height. I allow myself to make associations. The term water level comes to mind. The state of a water level. At what height does it become dangerous? What happens when it rises too high? What gets flooded? A village? A children’s playground? A sentence comes to mind, which describes this critical condition. The water is up to here. A limit is marked. This limit can be seen everywhere here. The stripes are coloured. The upper stripe is blue, and the one immediately below it red. The blue one reminds me of the water cycle, and the red one the bloodstream. These cycles are necessary for something to function properly. Life. I read the sentence behind the bath again ’Just as you speak into the water in the tub, when your mouth is blocked, so they speak to me. I am on the floor of the tub and they want to reach me from above.‘ I read it differently now, in connection with the water level marking. Now I understand that the limit has already been exceeded. A submergence has already taken place and the emergence is not yet clear, has not yet been decided.

The illustrations of the water surface also reveal something else about the subject. The surface, just like the stripes, makes a limit visible. The surface of the water as the supporting, the moving, the movable. Then there are also possibilities. Active possibilities – of immersion, of submersion. And of perishing. In the drawings, the depth of the water can also been seen on the surface. My gaze returns to the middle of the room. To the coat hangers hanging from the ceiling. Dresses and trousers made from paper are hanging from them. There are basins underneath the items of clothing. Some of them are filled with water. Clear water. Red water. Blue water. Some are empty. A women’s dress has already absorbed some of the colour from underneath. Some children’s trousers as well. New thoughts are pushed into my head. They hit each other like billiard balls, and roll on. Some fall into a hole. Others remain in play. The blank paper dresses and trousers seem like substitutions. I read them as models, and it is left open as to what they stand for. Yet, they definitely point to what we dress ourselves in and take off. How we colour ourselves in a way. A playing field. What can be put on in life and what cannot be? And which of those things can be removed and what can we not take off. To which cycles must we surrender? Is motherhood such a cycle? And can the colour be removed from such a cycle? Can the colouring be washed away? I am reminded of a quote by Judith Bulters, “The exclamation of a midwife, ‘a girl!’ is not only a constative assertion, but also a direct command, ‘be a girl!’”

The room falls quiet. The performance begins. The audience watch as Kinga Tóth and Doro Billard make noises with the water, with the paper. The paper clothes are sprinkled with water, submerged in the dye. Someone is taking pictures with a professional camera. I am in the way. I move slightly to the side, sit down on the floor and watch the two women. Not a word is spoken. The performance comes to an end. Chairs are brought in. There is now an opportunity to talk to the author and the artist about their collaborative work. People ask questions. Answers are given. I find out from Doro Billard that a dry cleaner is known as a teinturerie in French. If you were to translate it literally, it would be a dyeing factory. Interesting, I think. So when we want our washing to be cleaned, we bring it to a dyeing factory. Doro Billard explains that, as a child, she had always wondered why her father’s shirts came back white from a dyeing factory. The conversation is over. There is applause for the two women and I join in heartily. The work has really spoken to me, although not a word was uttered.